CUDA - Part 0 (Fractals)

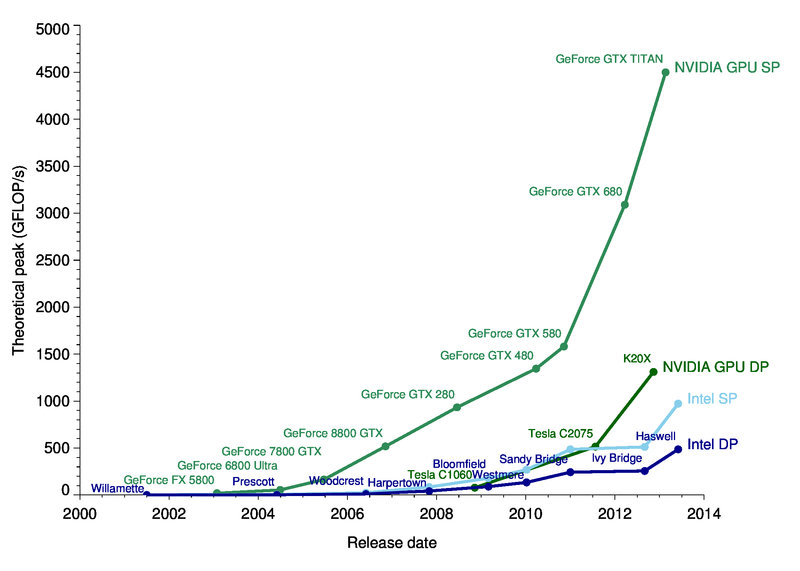

Recently I decided to learn CUDA programming (and generally about the GPU programming model). The motivation is that CPU performance is stagnating (certainly in terms of single threaded performance), while special purpose hardware like GPUs are becoming more and more powerful and useful. It seems that going forward for many interesting problems GPUs are going to become the standard platform of computation. Machine learning is an area that has seen great benefit from the power of GPUs, deep neural networks in particular. A lot of the computation involved in training neural nets boils down to matrix and vector multiplication, something GPUs are exceedingly good at.

The great thing about GPUs becoming a more mainstream computation platform is that the frameworks are much more user friendly than say 5 years ago, and there are great learning resources available. CUDA is a massive improvement in terms of usability over having to coax shader languages into doing something they weren’t really designed for. CUDA is basically a small extension of C, with a few caveats on memory allocation and access. One of the great things about it is you can compile the GPU code just as you would any other code, and benefit from static type checking and analysis. This is in stark contrast to what I remember of “old style” shader languages that were essentially strings embedded in your code that you “compiled” at run time and got back cryptic messages if anything went wrong. On the learning resources front I found the Udacity course on Parallel Programming to be fantastic. I thought the pace was perfect, not too fast or slow, and it covered everything you need to be able to write effective and efficient programs for the GPU.

CUDA Overview

Kernels are the main unit of computation in CUDA. These are basically functions that can be invoked from normal “CPU” code that will run on the GPU. The key thing to note is that kernel code cannot access variables or data stored in system RAM, it can only access data stored in device memory. This means that data passed to a kernel has to be either passed by value (so simple variables like integers for example), or have to be copied to device memory beforehand and a pointer to device memory passed to the kernel. One of the caveats that comes out of this is that you want to minimise the amount of data transferred back and forth between the device and host memory, as a ratio of computation that is performed on the GPU. For some classes of problems it may be that the cost of data transfer outweighs the benefits of processing that data on the GPU as opposed to the CPU. The speedup gained from using the GPU is negated by the cost of pushing data over the PCI-E bus. Alternatively, you may need to design your code in such a way as to hide the latency of the data transfer.

The other consideration is the way CUDA handles computation. The code inside a kernel is run on the GPU, with each thread of computation running independently and in a SIMD manner (more or less). The threading is implicit, in that each kernel is written as if it was for a single thread, and then the CUDA environment will span it across a large number of threads (with special variables accessible within the kernel specifying the current threads “coordinates” or id). A typical approach is to assign a thread to a given output index, and then the kernel should compute the value for that output location. The CUDA environment will take care of spinning up kernel instances to span the whole output. For example, if you are computing the product of two matrices, you could assign each thread to compute the value of a single element in the result matrix. In this case, the computation that each thread/kernel performs would be a dot product of a row and column of the inputs.

There are several caveats with CUDA (and GPU programming in general) to keep in mind to attain good performance. First is the fact that CUDA threads run in a SIMD manner, which means that branching has the potential to be quite expensive. It is ok to have a branch where certain groups of threads (called warps) take the same path, but if you have a case where a given thread may take an unpredictable path, then this can result in a performance penalty. The second main caveat is the effective utilisation of memory bandwidth. Ideally a given thread should perform a large amount of computation as compared to memory accesses. Memory accesses are fairly expensive in comparison, and often have go through a step of manual caching (using what is called ‘shared’ memory) to improve speeds.

As I found out later, naively implementing an algorithm in CUDA can be relatively straight-forward, but attaining good performance less so. You can sink a fair bit of time into optimising shared memory useage, minimising bank conflicts for memory accesses, and maximising coalesced memory access patterns. Quite fun though.

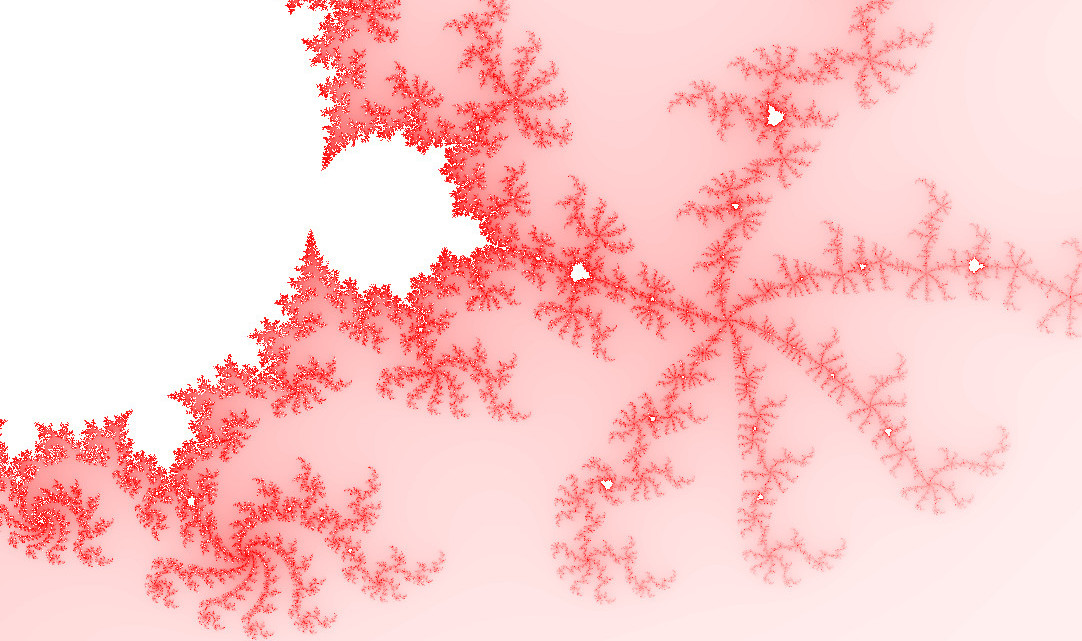

Fractal Visualiser

To get a bit familiar with CUDA I thought implementing a fractal visualiser would be an interesting project. The computation is trivially parallelizable (each pixel’s fractal set membership computation is independent), and I would get some nifty pictures at the end. One of the issues I ran into was avoiding thread divergence. Typically to compute set membership of a point, you would compute the recursive fractal formula in a loop, and every time check if the value is over a threshold distance from the origin and break out of the loop. As mentioned earlier, this doesn’t really work very well on a SIMD style processor. So instead I chose to iterate the recursive formula a fixed number of times for each pixel point, depending on the zoom level, and decide set membership at the end. This approach prevents thread divergence as each thread will be executing the same instructions.

The other issue I ran into is the high cost and latency of memory transfer. I chose to use the Cairo library for actually rendering the Fractal, so this required me to transfer the pixel value from the GPU to system memory, before rendering them to the framebuffer. This turned out to be a significant cost and adds about 100ms of latency per frame. Obviously this approach can be greatly improved upon by simply rendering the data straight from GPU memory, but it would involve a bunch of specialised code that I couldn’t be bothered writing as it is not directly relevant. The main point was to get an introduction to CUDA without getting bogged down in fine details.

In the end though, the CUDA code ended up being several times faster than CPU-based code (especially at higher zoom levels), despite the various optimisations I left at the table. Next up I’m going to implement my feed-forward neural network for handwritten digit recognition on the GPU. This is a fair bit more complex problem to implement than fractal rendering and should be fun.

The code for this project can be found on Github: here (warning: code is experimental and may be slightly messy).